Hey, quick announcement before I get into today’s topic…

Next week, I’m going to be promoting my Spotify growth membership.

I’m telling you this for three reasons:

Reason 1: I’ll be offering some cool stuff in the membership that I’m genuinely excited about, including brand new course materials and bonus trainings on topics like growing your own playlist, how my agency runs Meta ads, and more.

Reason 2: I’m using the old marketing tactic called “building anticipation,” the premise of which is that if you talk about a thing before the thing is available, people will get more excited about the thing. Think movie trailers, except obviously those are much more intentional and fun than my emails.

Reason 3: I know some of you are wholly uninterested in my Spotify growth membership, so I want to give you the chance to opt out of the upcoming emails. To skip all membership-related emails, just click this link. You’ll stay subscribed to this newsletter, and we’ll be back to regular programming the week following.

Okay – with that housekeeping taken care of, let’s get into today’s topic, which has (almost) nothing to do with Spotify marketing:

Is new music dead?

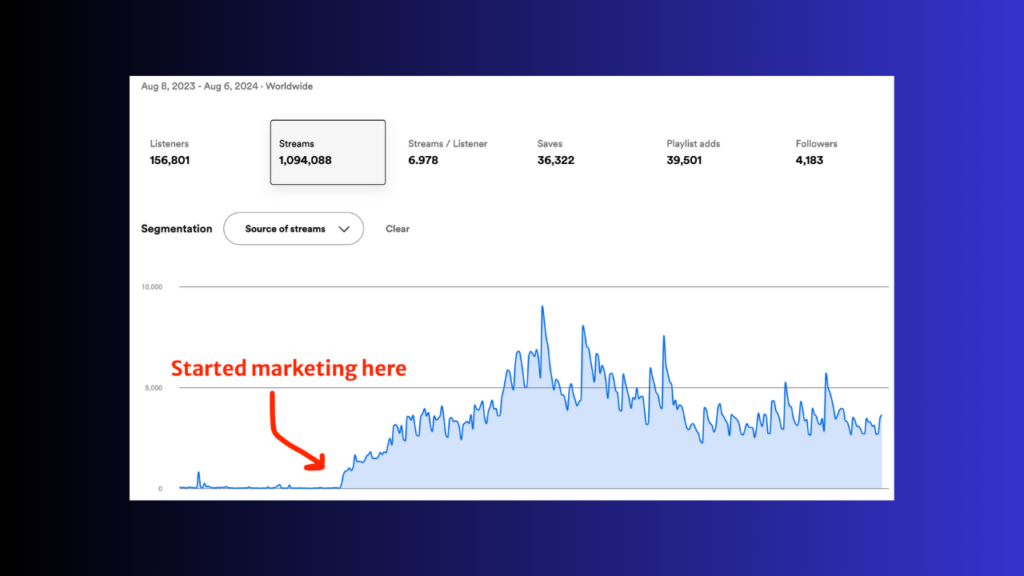

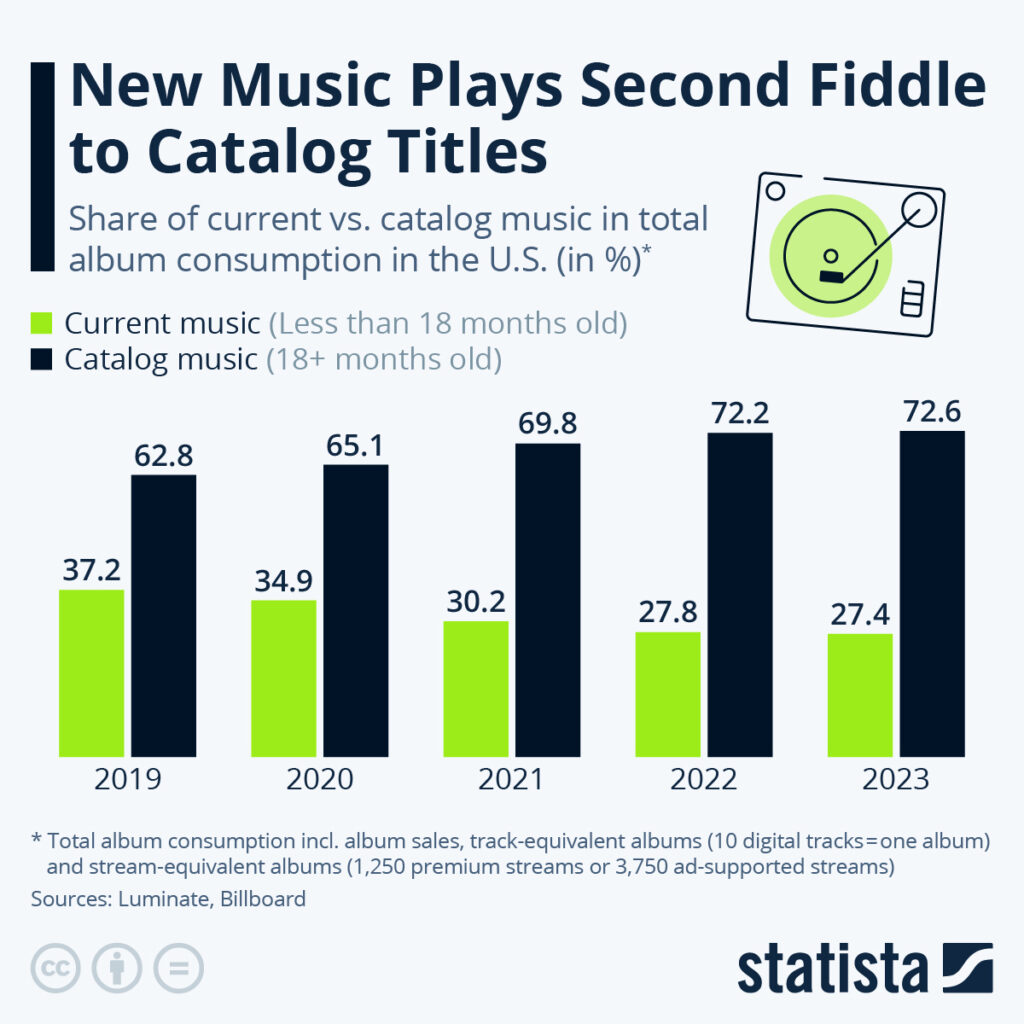

In the words of a 2010s-era Nickleback meme that still absolutely kills me, look at this graph.

For context, I got this image from Statista after seeing it in a Ted Gioia piece (which is a good read).

The takeaway from that graph: People listen to old music much more often than they listen to new music. And the gap is only widening.

That sounds weird, and for me it gives rise to two questions:

1) Why is this happening?

2) What does it mean for artists?

Don’t worry; I’ll give you my two cents on both of those queries. While our culture is complicated, I’m 95% sure that after thinking on this for twenty minutes, I’ve got everything totally figured out.

Why are people listening to less new music?

I think context is helpful here. In Gioia’s piece, he positions the old music trend as part of our broader culture: Across the arts, we’re seeing an increased recycling of old material.

Movies, for example, are more likely to be sequels than ever before. Actors in movies, on average, are older than they were a few decades ago.

Last year, 73-year-old Bruce Springsteen orchestrated the third-highest-grossing tour on the planet. He was behind, of course, Taylor Swift’s “Era’s Tour,” which was focused on supporting her catalogue of releases dating back to 2006.

It’s all a little disconcerting, and it’s happening everywhere you look (even, I’ve heard, in politics). So, again: Why is old art getting more attention than new art?

I think that the two driving factors in this trend are media fragmentation and cultural mummification.

Let’s start with media fragmentation.

At the beginning of this year, I wrote about a concept from Hit Makers: The biggest human bias is familiarity. We’re more likely to pay attention to what we already know.

New art has always been a risk to produce because it’s inherently unfamiliar. But it used to be that studios could manufacture familiarity pretty easily. In 1975, you could just pay the mainstream radio stations or get on one of the big three TV networks, and everyone would know the name of your new artist in a matter of weeks.

In 2024, familiarity is much harder to manufacture.

There simply aren’t mass broadcast channels in the same way that there were for most of the 20th century. Streaming services and social media platforms have shattered the fragments of mainstream media into fine grains of sand; now, you only see what you want to see. (Or, more accurately, you see what your apps have determined you’ll pay attention to.)

The old levers of power no longer exist. But the old art that benefited from those levers of power still does.

And that leads me to my second point.

The internet has mummified all of culture.

Everything is preserved forever.

Here’s what I mean. Imagine that you’re a kid in 1980 with a love for old-time rock and roll, and you decide that you want to watch Buddy Holly performing “That’ll Be The Day” with The Crickets.

Well, I’ve got some bad news for ya, sport: You can’t.

The only way you’d be able to watch Buddy Holly in 1980 would be to stumble across a rerun of the Ed Sullivan show or crank a classic radio station for hours on end. Maybe you can plan your day around something like that happening, but in 1980, you certainly don’t have that specific piece of art available on demand.

Now, fast forward to June 10, 2024, and imagine that right now, as you sit here reading this newsletter, you want to watch Buddy Holly performing “That’ll Be The Day” with The Crickets. Good news, champ! You can, anytime, anywhere, forever.

All culture since the creation of the phonautograph has been mummified for your listening and viewing pleasure.

Here’s the kicker:

Because old art is already familiar (since it’s already benefitted from the powerful old broadcast mediums and the passage of time), audiences are more likely to pay attention to it.

And that means social algorithms are more likely to show it. And that studios and labels are more likely to value it.

And on it goes.

So what does this mean for music artists?

It means the world is sad and probably ending soon, and you should quit making music since clearly it’s not worth it anymore.

I’m kidding. I’m not that pessimistic.

Realistically, this does mean that it’s less likely you’ll be the next Taylor Swift. It’s just increasingly hard to get mass market awareness. But come on – even thirty years ago, your odds for being Taylor Swift were pretty slim. I mean, look at you. (Kidding, kidding.)

I think it’s important to note two things.

First, as Gioia and many others have noted, the fragmentation of mainstream culture has coincided with the rise of micro culture. While there are fewer huge new artists, there are also simply more artists than ever before. As Spotify trumpeted earlier this year, more artists than ever are making a living from streaming royalties (including a growing segment of mid-tier, indie artists).

Kevin Kelly’s “true fans” concept (which I’ve critiqued before but which I still very much like) is being lived out by more creators each year. You can live it out, too, even if you probably won’t be T-Swift.

I think this whole micro-creator aspect of our cultural drift is hugely encouraging.

Second, I’m going to hop back on my hobby horse and remind you that the value of art is real but not easily quantifiable.

So sure, old music is more valuable in monetary terms than new music – we’ll let them have it. That doesn’t mean old music is more valuable, period. Music (like all art) is a means to relationship and an end in itself. The point of making it is not to reach the largest audience possible.

The point of making it is to make it.

Okay, that’s all for today.

Glad we’ve figured all that culture stuff out. For those of you who are interested, I’ll be back next week with a bunch of more practical stuff about my Spotify growth membership.

For now, get out there and make some new music. It’s worth it.