When I was a kid, I thought I wanted to be some version of a rockstar.

I say “some version” because I didn’t actually want to be a rockstar; even as a kid, I was always more inclined toward soft-indie pop or folk music. I’m about as rebellious as an unsalted oyster cracker.

But I did, in a general sense, want to be a star.

I wouldn’t have told anyone this – especially not my high school guidance counselor – but I wanted to write songs and have people I didn’t know sing them back to me. I wanted to be asked for my autograph and have stacks of my CDs for sale at Walmart. I wanted to play music in huge arenas, or at least two-thousand-cap theaters, or at least larger-than-average coffee shops.

Or at least, I thought I did.

Looking back, I’m pretty sure that I wanted those things mostly just because I wanted to play music. Most of my desires related to a music career were shaped more by cultural osmosis than by any internal spark or serious thought.

I watched American Idol, and a little MTV, and even Camp Rock, and from there I half-consciously spun out a funhouse-mirror version of what was required if a person wanted to make music throughout their life:

- Fame.

- Fortune.

In fact, what I believed about a music career as a kid could be boiled down to this strict dichotomy:

If you wanted to make music, you either became a famous musician or you failed. There was no middle ground.

I’m 31 years old now. I’m not yet famous, but I am much more cynical (and I’m holding out hope that I might also be a tiny bit wiser).

I’ve been thinking recently that the dichotomy I subconsciously bought into as a kid was mostly a bill of goods.

You don’t have to make it to make music.

Here’s why.

First, let’s state the obvious (and I hope this line of thinking will make the problem clear):

You can make music for the rest of your life whether you receive any external validation or not. There’s nothing (that I know of) stopping you. So, clearly, you do not have to be famous to make music.

Obvious, right? But this obvious fact is countered by an overwhelming and sad reality:

Most people who are not trying to make it with music no longer make music.

Do your parents make music? Do your friends?

How many people can you think of who actively make music and are not trying to make music their career? If you’re like me, the answer can be counted on both hands.

This is sad, because music is not, like soap carving or stamp collecting, some niche hobby for the strange few. To be a person is to make music. There’s a strong case to be made that humans sang before they spoke. I heard someone say recently that, if you ask a kindergarten class how many of them sing, you’ll get a room full of raised hands. But if you ask a college class the same question, you’ll get only a handful.

Somewhere in grades one through 12, we learn that we must outsource a fundamental part of our personhood to pop stars.

I’m sure there are many causes for this. But I think one contributing factor is the dichotomy our culture sells: Either you do something full-time for money, or you give up doing it.

We buy this dichotomy because our culture has incorrectly answered a question most of us have never consciously asked:

What is music for?

Mostly, I think, our culture views music as a commercial product.

It’s something to be bought and sold (or streamed and not paid for, as the case may be). If it’s for anything, it’s for entertainment. You put it on to make the world a bit more bearable while you’re stuck in traffic or doing the dishes.

If music is primarily a commercial product, it makes sense that we would leave its production to the professionals. They are, after all, better at making it than we are.

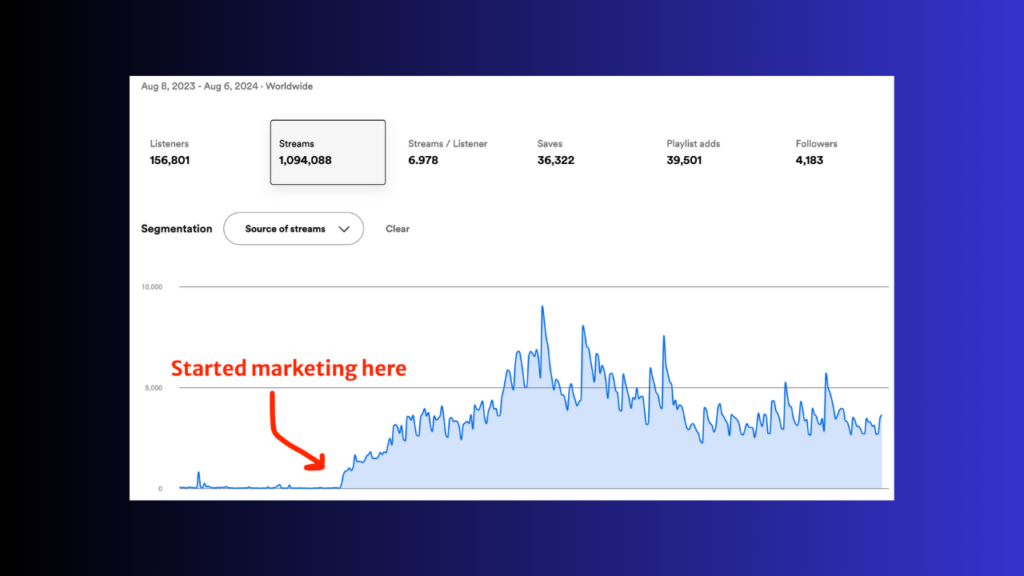

It also makes sense that our primary gauges for the success of music culture are financial outcomes: Is the music industry making more or less money than it did a decade ago? How much of that money is allocated to new acts? Are streaming payouts saving artists, or are they too low?

Articles about these sorts of issues are everywhere (like here and here and here). Much more rarely does anyone seriously ask the question: Is the music our culture is making any good?

And this brings us back to the problem.

Look, I don’t claim to corner the market on truth. I’m not proposing to tell you, in absolute terms, what music is for. But my guess is that most of us, after a moment’s thought, would agree that music is for more than money.

Personally, I tend to think that music is for relationship.

More specifically (as with all good art), it’s for the communication of genuine emotion. It’s for a mother singing comfort to her child. It’s for protestors singing anger to the world and to each other. It’s for the church and for God. It’s for the pouring out and taking in of love, sorrow, joy, laughter – everything it feels like to be human.

If that is something close to what music is for, then there is good reason to make it.

Even if you are paid fractions of pennies to do it.

Even if you never make it for a full-time living.

A friend of mine who is a songwriter wants to help other people write songs.

The idea, he says, is not to make another songwriting course for self-identified musicians (although there is plenty of good in that). The idea is to help people who are not musicians write songs. This is the goal because, in my friend’s view, songs are worthwhile whether they are commercialized or not. The people who write songs, he thinks, will find themselves and their relationships healthier for the work.

You’ll be unsurprised to hear that I told him to go for it.

I’m aware, as always, that I’m writing all of this in a music marketing newsletter.

And I know many of you are on this list because, at some point or another, I promised to help you make a career out of your music.

But as I’ve listened to the (fair) complaints about the industry’s pitiful royalty payouts, and responded to the defeatist comments on my posts about music promotion, and read the ham-fisted hype articles about AI, I’ve found myself drawn back up again and again to what’s become my main soapbox:

Music is an end, not a means. It’s not for fortune or even fame. It doesn’t exist to help creators have careers. It has always mattered for more than money.

In the same way that it’s good to have friends, it’s good to make music.

I hope these thoughts are helpful as you think through your own music-related goals.

On top of that, I hope you don’t think I’m too hypocritical when, later this year, I re-launch my musician income survey to find out how artists actually do make money.

(“How do I make money from my music?” is one of the most common questions I get. It’s different from the question, “What is music for?”, but that doesn’t mean it’s not important and worthwhile to answer.)

All right, that’s all the philosophizing I’ve got in me today. I think most of what I wanted to say is: Keep making music.